- New research reveals the dire threat that climate change poses to coral reefs, one of the most important ecosystems in the world.

- Within 20 years, 70-90% of coral reefs will likely die. By 2100, there could be few to none left.

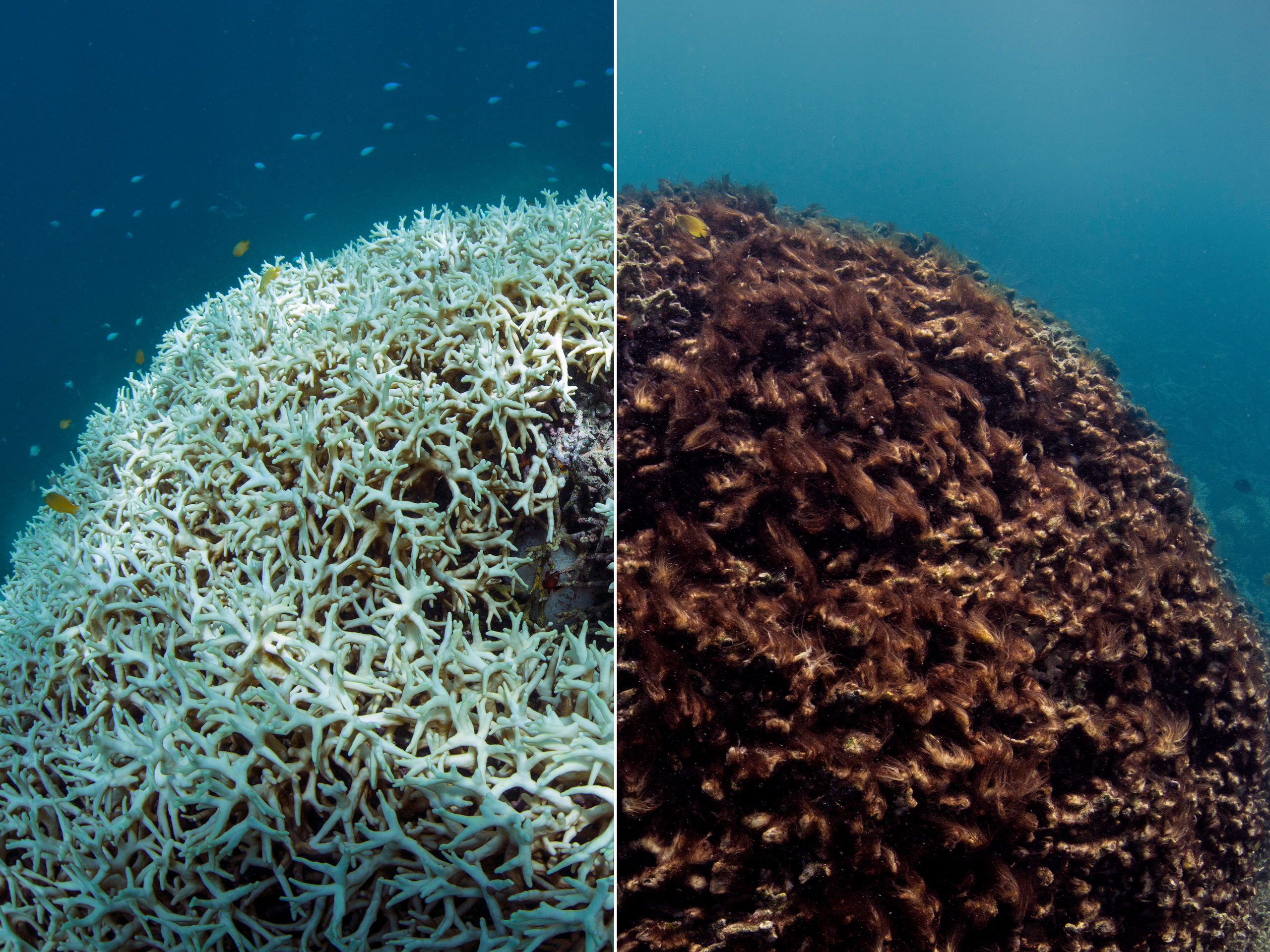

- Photos show what vibrant reef systems currently look like, and what could happen to them in the future because of climate change.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Coral reefs are dying.

Between 70% and 90% of all reef systems could disappear within the next two decades because of pollution and climate change, according to new research.

That projection, which researchers from the University of Hawaii Manoa presented at annual Ocean Sciences Meeting last week, suggests that by the end of the century, there could be few to no suitable sites for coral reefs anywhere in the world.

Coral reefs cover less than 1% of Earth’s surface, but they provide a home for over 25% of all marine life. Millions of people rely on them for food, medicine, protection from storms, and employment in tourism sectors.

But corals are highly sensitive to water temperature, and climate change is causing oceans to warm and become more acidic. Some studies suggest half of the world's coral reefs have already died.

The new research also found that by the end of the century, there will be very few locations where human efforts to restore coral habitats would be viable at all.

"Trying to clean up the beaches is great, and trying to combat pollution is fantastic. We need to continue those efforts," Renee Setter, the lead researcher on the project, said in a statement. "But at the end of the day, fighting climate change is really what we need to be advocating for in order to protect corals and avoid compounded stressors."

Here's what bright, biodiverse coral reefs look like, and the dead shells they could become.

Coral reefs are often considered "rainforests of the sea" because of the diverse array of creatures that live in them.

Australia's Great Barrier Reef is the largest and most extensive reef system in the world. But half of it was killed off in two consecutive years of coral bleaching in 2016 and 2017. It's currently facing another.

In 2016, one-third of the 3,863 reefs in the Great Barrier Reef system went through a catastrophic die-off after an extreme heatwave. A bleaching event the next year devastated even more reefs; the cumulative effects have killed an estimated half of the Great Barrier Reef.

The new research projects that reefs could cease to exist by the end of the century if ocean warming continues.

The blue staghorn coral in the image is experiencing a bleaching event. When healthy, it ranges from vibrant turquoise to royal blue in color.

"The bright blue staghorn coral is not normally that color. It is fluorescing - another sign a coral is in distress," Lyle Vail, director of a research station in the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, said in a statement from the World Wildlife Fund Australia.

As waters warm, coral loses the algae that lives in its tissue, provides nutrients, and gives coral its bright color — a process called bleaching.

Bleaching doesn't completely kill coral, but it makes reefs vulnerable to toxic algae, disease, predators, and death.

Oceans also acidify as they absorb more carbon dioxide, and that causes bleaching, too.

Some estimates suggest that about half of the world's healthy reefs have already been killed in the last 30 years.

Runoff from agriculture and pollution from nearby cities pose additional threats to reefs.

A proliferation of crown-of-thorns starfish in the Great Barrier Reef in 2018 was caused by nearby fertilizer runoff, which helped the starfish breed. Overpopulation of these predatory starfish can ravage coral reefs.

The coral, meanwhile, was experiencing bleaching events that made them weaker and more vulnerable to attack.

In the Pacific Ocean, overfishing has thrown food chains out of balance. The overharvesting of reef fish removes the natural consumers of some seaweed-like algae, allowing it to grow to levels that can smother reefs.

According to estimates from the World Resources Institute in 2011, 55% of the world's reefs are threatened by overfishing, with nearly 30% considered highly threatened.

Fishing boats also drag nets that entangle live coral and tear them away from their bases.

Boats' anchors can damage and destroy reefs, too.

Scientists and policymakers have tried to protect coral by banning sunscreens with toxic chemicals and encouraging divers not to touch reefs.

Some marine scientists are also trying to build reef "nurseries" from equipment like old ships or concrete blocks that young coral — usually raised in laboratories — can grow on.

The researchers at the University of Hawaii Manoa attempted to map out future locations that would be suitable for coral restoration efforts

Their models took into account future sea-surface temperatures, wave energy, water acidity, pollution, and overfishing.

The study found that by 2100, there will be "few to zero" suitable coral habitats.

The few sites that could support reef restoration were in Baja California and the Red Sea.

But even those are not ideal reef habitats because of their proximity to rivers, the study found.

"Honestly, most sites are out," Setter said in the release, adding, "by 2100, it's looking quite grim."

Environmentalist David Attenborough spoke about his first time scuba diving in the Great Barrier Reef in a BBC interview: "Below me there was a wonderland — a coral reef. On it, there were fish I never dreamed of, with colors I could only imagine, and there were all these other organisms that I had never seen before in my life."

Future divers, however, are unlikely to enjoy the same sights.